Ehsan Abdollahi is an Iranian artist who stands at the intersection of science, nature, and creation.

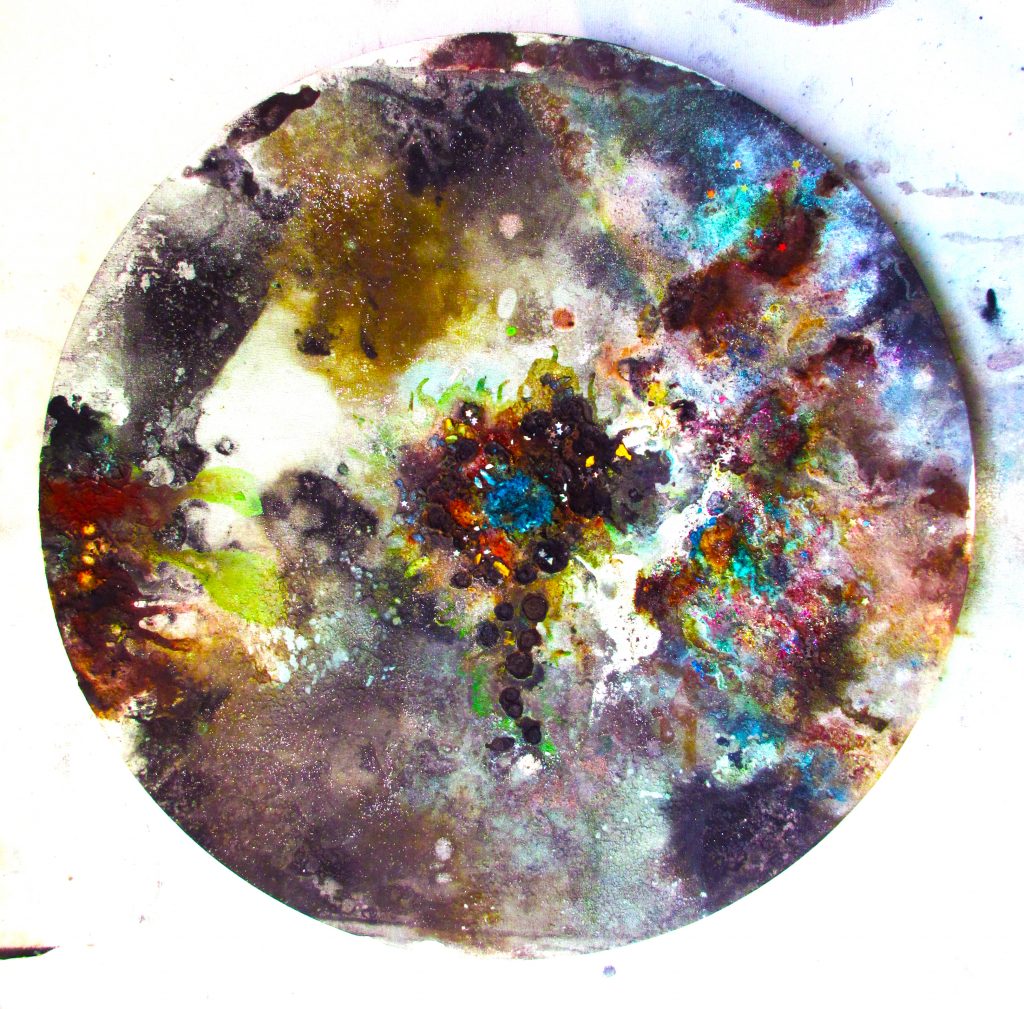

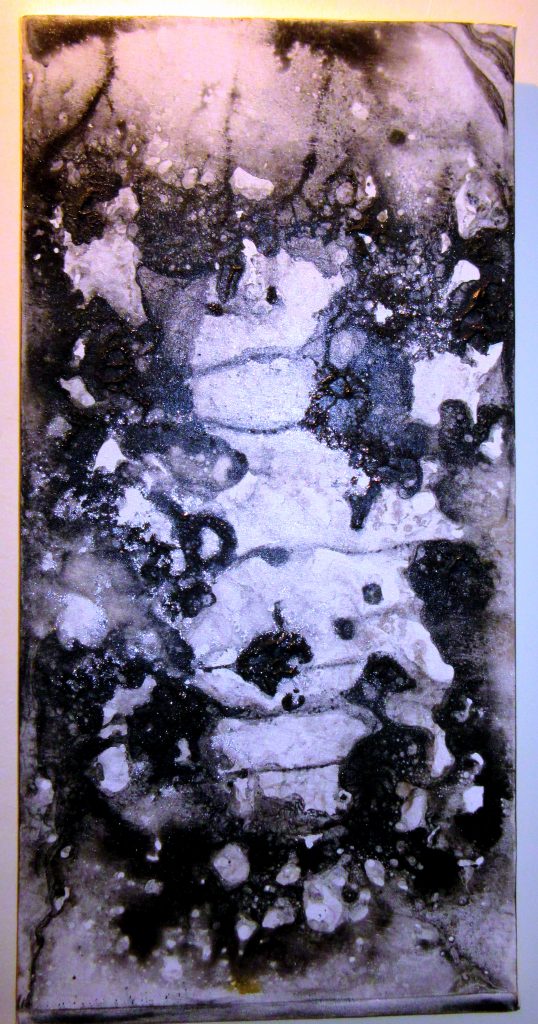

His works are created without using artificial pigments or traditional painting tools, only through the chemical reactions of natural elements such as silver, iron, manganese, copper, light, water, and oxygen.

He is the founder of the Alchemy/Povera style, an approach in which nature is not only the inspiration but the creator itself.

His works are a living dialogue between matter, frequency, and consciousness, where every canvas speaks to the audience as a mirror of the Earth’s soul.

Together with his brother Mohsen Abdollahi, he is the co-founder of Modern Industry’s Life and the environmental platform Earth CPR, a technology based on nanobubbles and nanocatalysts that restores soils contaminated by petroleum and chemical compounds, rescuing the planet from biological coma and industrial suffocation.

«In childhood, I dreamed of saving the Earth from poverty, injustice, and destruction, but I always thought it was impossible.

Until the day my brother Mohsen discovered a way to restore nature through science.»

He believes that art can do what science does: awaken the Earth.

In his works, science and creation meet to build a bridge between humanity and nature, between the mind and the universe.

«When I saw polluted soil breathing again, I realized that perhaps art could help awaken the inner consciousness of humanity.

From that moment on, my path and the Earth became one, in science, in art, and in faith in regeneration.»

Do you remember the first experience that showed you that matter can paint by itself?

Yes. During scientific experiments with my brother, while we were combining elements to create a powerful nanocatalytic structure for soil regeneration, living and autonomous shapes and textures began to appear.

At that moment, I felt that the Earth was revealing something from within itself, not a design by me, but a revelation of the material itself.

That was when I realized: I am not the only painter; science also holds the brush.

How does life in Tehran influence your choice of elements and the creation of your works?

Tehran is a living being to me — full of contrasts, full of pulse.

Smoke and light, cruelty and kindness, chaos and life. All those contradictions flow within me as well.

I use its soil and pollution for creation; from the pain of its wounds, I make the ink of truth.

With all its noise and chaos, Tehran leads me to inner silence, where I can hear the voice of nature more clearly.

How do you perceive this vibration? Has there ever been a work that “sang” louder than the others?

Each work has its own unique frequency and sound.

These sounds are real and even measurable on a physical level with noise-filtering devices.

Some pieces vibrate at low frequencies, others at high ones, but those formed through the reactions of earthy and metallic materials actually sing.

It is as if the spirit of the Earth is humming the lullaby of its own rebirth.

How do you balance artistic intention with respect for nature?

My intervention is minimal. I force no material to behave.

The reactions occur naturally in their own time, temperature, and humidity.

I merely create the conditions for nature to express its own creativity.

Even the failure of a reaction is sacred to me because it is a sign of life.

For me, art is not interference; it is companionship.

If someone touches one of your works for the first time, what feeling would you like to arise in them?

I want them to feel the birth and rebirth of matter and nature —

a sensation like rebirth, that sacred moment when the soil comes alive again.

Each touch should be like the Earth awakening: a blend of warmth, vibration, and awareness that recalls the unity between science and art.

If, in that moment, the viewer feels they are part of the cosmos or of the Earth itself,

and hears the whispers of existence within their own being,

then the painting has fulfilled its mission.

Do you have a funny anecdote?

When I go to buy raw materials for my works, I’m always met with astonishment and curiosity. Not only is sourcing these materials difficult and time-consuming, but shopkeepers are often surprised by the unusual combinations I request. Once, a shop assistant jokingly asked me, “Are you making drugs or building a bomb with this?” I laughed and replied, “No, I’m coloring the world.” That moment perfectly captured the gap between common assumptions about “art” and the reality of my practice: turning natural reactions into a new visual language.